The Day of Iemanjá

The neighborhood where I live in the south of Florianópolis, Brasil, has gentrified rapidly in the last dozen years: luxurious apartment buildings, closed condominiums, chique restaurants and boutiques. Last night, to my great joy, those new walls served as the sounding box for drums calling people to the beach to give thanks to Iemanjá, the orixá of the ocean.

Thousands of people walked down the main shopping street of Campeche until it opened onto the beach. Many sang in Yoruba, the Nigerian language preserved in afro-Brazilian rituals. Others clapped in the rhythm of the ijexá. Six ogans — drummers and priests in the candomblé and umbanda religions — carried a boat made of banana laves and palm fronds, filled with flowers and a statue of Iemanjá.

As the procession poured onto a beach already starred with hundreds of candles protected from the breeze by low barriers of sand, people ran to the water to throw flowers into the waves. Some — both black and white — were clearly congregants of the local afro-Brazilian religious communities, marked by their white clothes, turbans, or long strings of ceremonial beads. Many more were not: Iemanjá and her rituals have become a part of Brazilian culture that reaches far beyond religion.

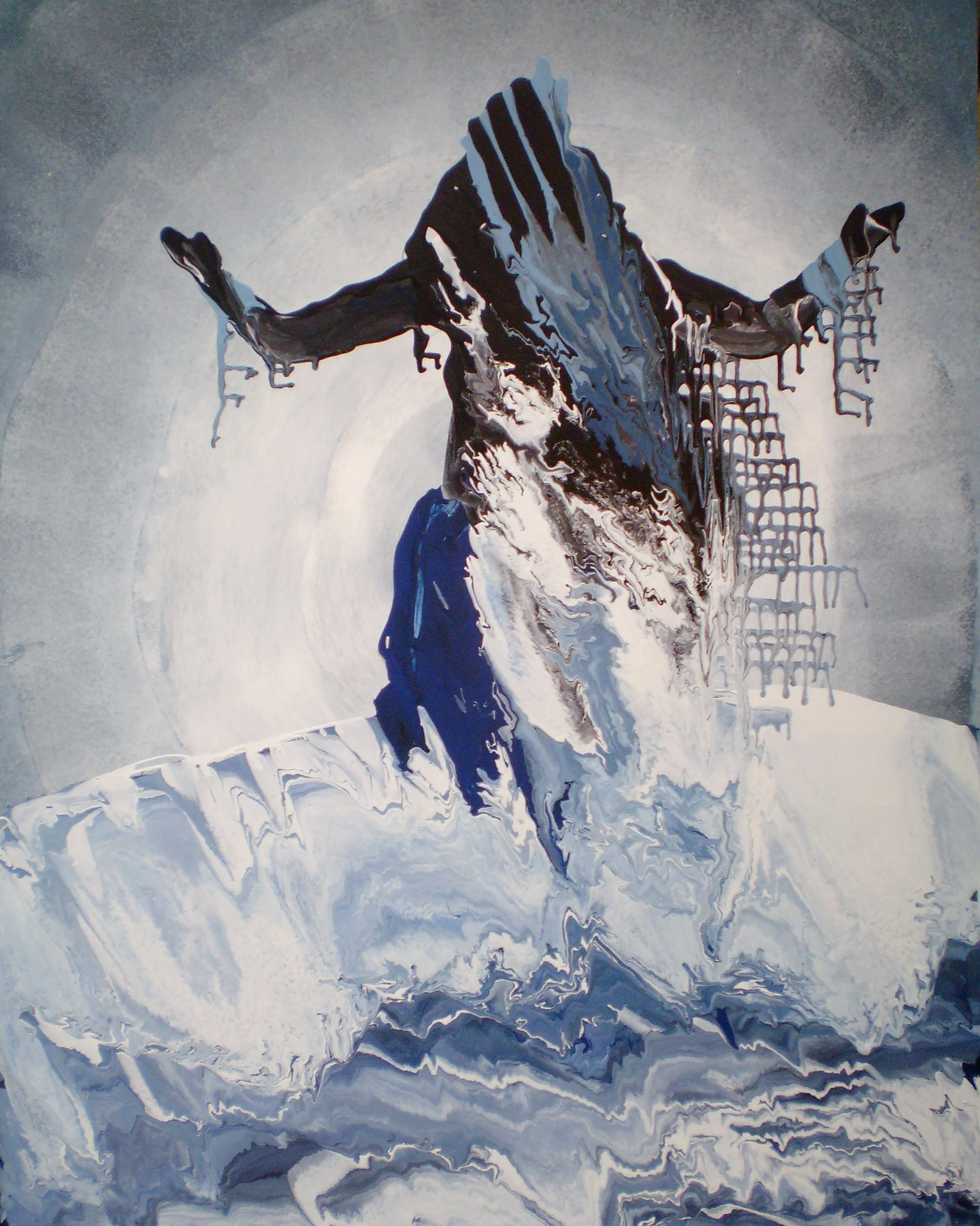

The mãe de santo who had organized the procession — a religious leader whose small temple sits behind her house on a dirt road that runs up the hill close to our house — brought the ritual boat into a tabernacle on the beach, where the believers sang and prayed. Then suddenly, the boat — now without the icon of Iemanjá among the flowers — exploded from the tent and was carried down to the beach and launched into the water. Hundreds of people followed the boat into the breakers.

Drums echoed against the beach-font restaurants: a tambor de criola organized by a woman from the norther state of Maranhão; a samba de roda where young dancers would leap into the circle to compete one-on-one with fast, elegant steps. The beach became of happy anarchy of dancing, of rhythms, of children running into the water, building sandcastles, falling asleep exhausted on the beach towels their parents had brought. We ran into one old friend after another: Helena’s music teacher from when she was a little girl, a young actress from our last movie, a young man who makes huge carnaval puppets of bulls and vultures, our representative to the state legislature…

In 2026, middle class Brazil seems to have been tamed into the modern, European world, but something wonderful and magical still lies under that surface: yes, the joy of the drums and the dance, something that now seems lost in the middle class domesticity of the United States and Europe, but also the spontaneity of encounter, an unpretentious being-together on the beach where you chat with old friends or the new conversations in the procession where you make new ones. When one says “ritual” or “procession” in English — even a word like “religion” — it sounds heavy, serious, ponderous. The night’s celebrations for Iemanjá were anything but: they were playful and fun, full of laughter, young dancers flirting, children running in circles as their parents shared a beer or a cachaça.

In his “The work of art in the age of its mechanical reproduction,” Walter Benjamin famously compared a saint’s processions in an Italian village to the new art of cinema. There is only one icon of the saint, Benjamin insisted. It comes out once a year, carried through the city on a special day by special people under special rules. A movie or a photograph, in contrast, can be reproduced millions of times: it is not limited by place, community, or context. The “special” and controlled art of the saint’s icon, then, gives it a powerful aura, something unique and potent and even magical. When art becomes reproducible and easily available, Benjamin insisted, something fundamental was lost — and something gained: he saw a change for political change in this new way to live art.

I’m not part of a candomblé terreiro, but two days ago I was invited to help build the boat that would carry the icon of Iemanjá to the ocean. As I experienced the hierarchies and prohibitions of the terreiro, Benjamin’s idea of aura made even more sense: I was not allowed to step in certain places, prohibited from sitting in the chairs, permitted to use a knife to cut the palms and banana leaves only outside the temple. Then the procession to the beach, full of drums and ritual chants in a language I do not understand, felt like those saints’ ceremonies in Italian villages. Iemanjá had an aura around her.

At the same time, the procession felt new and wonderful, perhaps even magical. The singer and many drummers stood atop a trio elétrico, a particularly Brazilian kind of truck filled with top-end loudspeakers, designed with carnaval parades in mind. Drones flitted overhead, not police surveillance but the young filmmakers from the terreiro, wanting to document the amazing event they had created for the community. The boat-builders, thinking ecologically, made their ritual barque from materials that would biodegrade quickly. Not to mention that the procession went along a modern shopping street, full of bars and clothing boutiques, not the ancient allies of a medieval city.

But perhaps the most magical part of the event was also the most digital. As the ogans carried the flower-filled boat into the breakers, hundreds and hundreds of people ran after it, their cell-phones held high to record the ritual for their friends, for instagram accounts, for family WhatsApp groups. The low lights of the cell phones mirrored the candles in the beach, a pale reflection of the full moon overhead. Paradoxically, what gave the aura to the event — its sense of importance and joyful weight — was the attempt to digitally reproduce it. Social media is the apotheosis of Benjamin’s reproducible art, something with no aura at all. And yet the creation of content for social media gave the procession the aura of magic and moment that made it something different, something outside the normalcy of the day-to-day.

Spend much time on the internet these days, whether reading news or doom-scrolling social media, and you might start to despair. Last night gave me a glimmer of the reconstruction of hope.